OUR STORY

Daisy, Benito, Luby, Sadie, and Paul Apodaca @ El Chapultepec late 1940’s.

Chapter One: The Early History

In 1933 America ended the “noble experiment” of prohibition. That same year, Charlie Romano opened El Chapultepec as a bar and restaurant. While there are many theories about the origin of the name, eventual owner Jerry Krantz would confirm that it’s unique and “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” So, El Chapultepec it remained through all the years. Rumors say that The Pec served as a speakeasy before that time, but nobody can officially confirm. The trap door behind the bar leading to an underground exit lends to this theory. The neighborhood was seedy with rows of bars lining the nearby Larimer St, including Herb’s Bar which celebrated 90 years in 2023. A hotel straight out of a western movie was next door on 20th, now home to the Giggling Grizzly. Two doors down on Market St was an infamous brothel, Mattie’s House of Mirrors. The freight train ran 20 feet from the front door, and even up through the late 1980s, The Pec had to close at midnight on Sundays for the inconvenient and dangerous passing of the train. At some point, Charlie Romano’s son, Tony Romano, took over El Chapultepec.

Jerry Krantz, a Denver native, served in the USMC during the Korean War as an underwater demolition specialist. He was discharged in the early ‘50s and went to Chicago to find work. It so happened that the work he found was at a Jazz Club. Jerry wasn’t big on talking about himself, but jazz was something he loved. The details are ambiguous, but we do know that Chicago is where he became great friends with prominent musicians (such as Red Holloway) and fell in love with the intimate jazz club model. Upon his return to Denver, Jerry started courting and eventually married Tony Romano’s daughter, Julia.

Jerry started helping out at El Chapultepec in the late 50’s while simultaneously being a cabbie and owning a dog food company for racing greyhounds. When Tony Romano fell ill, Jerry took the helm and eventually ownership of the bar (although the Romano family never sold him ownership of the building). Through the ‘60s and ‘70s, Jerry kept most of El Chapultepec the same. It was a working man’s bar. A simple shot-and-a-beer kind of place with Mexican fare and mariachi performances. Jerry’s wife unfortunately passed away from health complications. Mariachis were getting harder to book and Jerry longed for that feeling of live jazz that he experienced in Chicago. While Denver had a lot of live jazz, it was for the rich. Dick Gibson had black tie affairs, the country clubs brought in acts, and the symphony orchestra was a formal event.

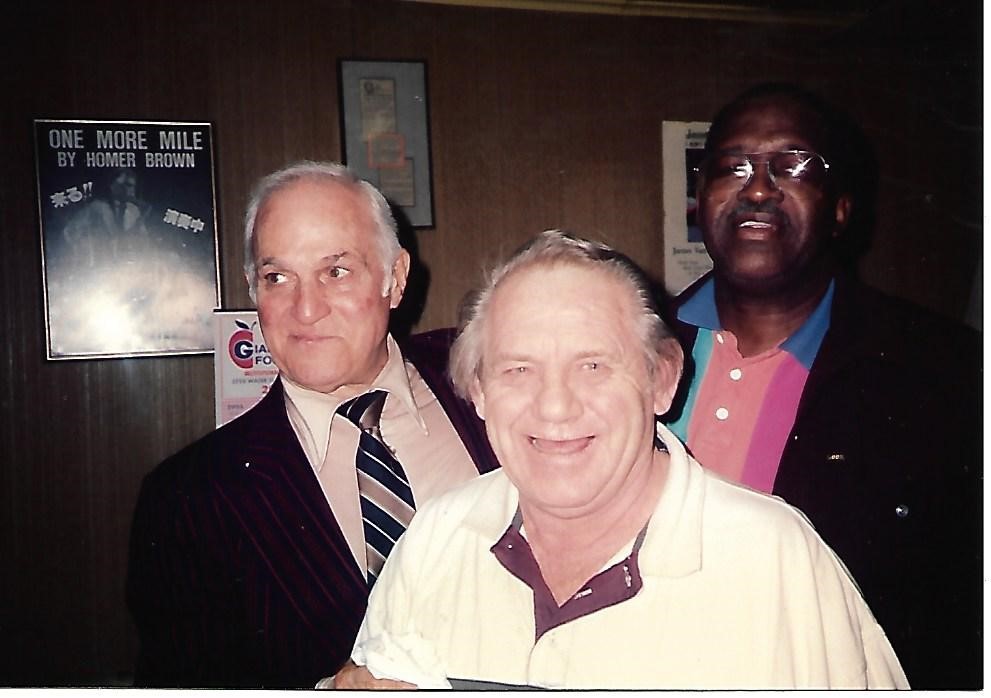

Pete Condoli, Jerry Krantz, Ed Battle in the Pec Office late 1980’s

Pete Condoli, Jerry Krantz, Ed Battle in the Pec Office late 1980’s

Chapter Two: Cool Jazz and Hot Burritos Nightly

In the late ‘70s, Jerry approached some local jazz musicians who were gigging around town at the time. One of them was Freddy Rodriguez Sr., a prominent local jazz saxophonist. In Ben Makinen’s documentary Jazz Town, Freddy laughs when reminiscing about the offer and says, “it was a dump!” Yet, they gave it a try. In 1980 Jerry married Alice and together they built the El Chapultepec legacy while raising a family. Alice ran the kitchen while Jerry ran the bar. All of the kids (Tony, Ray, Angela, And Anna) were in the bar most of the time. But Angela in particular loved being with her dad. She started working in the kitchen around 13 years old and was running that side by the time she was 18.

Jerry’s idea was to offer live jazz with no cover charge, a two-drink minimum per-person per-set, no reservations, first-come first-serve, no dress code. He wanted the everyman to have access to experience the magic of live jazz music. And people fell in love. They kept coming back. The more people asked for the music, the more Jerry would book. Soon, El Chapultepec was hosting live jazz seven nights a week! Jerry always kept the Mexican fare for the same reason as the name: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. The unusual combination graced the outdoor mural for decades.

“Hot Burritos and Cool Jazz Nightly.”

Once the word started to spread, droves of musicians started coming by to check the place out, too. On Sunday, July 10, 1983, The Rocky Mountain News ran a front page story with the headline “Music packs ‘em in at El Chapultepec.” In the article, Jerry talked about how he chose house bands who had chops and could hang with any of the best in the world. And sometimes, they did. Jerry recalled a time that the Tommy Dorsey Band was in Denver for a gig. Afterwards, they showed up in three cab loads and stayed for two days playing with the house band. When asked about the success he said, “We did it right. We got the best local musicians – people like Freddy Rodriguez, Bob Montgomery, Bruno Carr, Gene Bass, Phil Urso. And though I never told anyone what to play, they concentrated on the standards. Tunes people know. Straight ahead jazz. Not too much fusion music. And I refuse to charge a cover at the door or $4 for a drink. Now everybody comes here.” That was a recipe that served up over four decades of live jazz at El Chapultepec.

Through the next four decades, El Chapultepec saw just about every jazz musician a person could name. From the old-timers who blazed jazz into the mainstream, to the young cats who were just learning to shed wood. El Chapultepec’s stage was a magnet for all of them. Those who came to sit in had better been ready to swing. Long-time house band leader Billy Tolles would be heard telling someone who didn’t make the mark to, “go lose your own gig, I’m keeping mine!” It became a sort of rite of passage or badge of honor to sit in with the band at El Chapultepec.

Four generations of jazz greats graced the stage. Some of the first-generation guests were Freddy Hubbard, Doc Severinsen, Chet Baker, Art Blakey, Etta James, Al Grey, Ike Cole, and almost the entire Tonight Show Band (including the Condoli brothers and Pete Christlieb). Second generation guests included all three Marsalis brothers, Harry Connick Jr. with his whole big band, Natalie Cole, and Chick Corea. Some third generation Pec guests included Ben Markley, Andre Mali, Tenia Nelson, Gabe Mervine. The fourth generation is just coming of age. Many are children or grandchildren of the generations before them. Honestly, the list is so extensive that it’s impossible not to leave people off. Furthermore, the talent who lives in Denver rivals that of NYC and LA. Many national recording artists call Denver home and dozens of them have held residency or sat-in regularly. We hope to devote a part of the El Chapultepec legacy project to compiling a comprehensive list.

It wasn’t just jazz musicians who fell in love with The Pec, either. Musicians of all genres and celebrities of all kinds enjoyed it. Some of the patrons included The Police, ZZ Top, Mick Jagger, Dave Mathews, Santana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bill Clinton, Christopher Walken, Pat Morita, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Andy Garcia, Michael Madsen, Scott Hamilton, Ed Sheeran, Dierks Bently, and so many more. Jerry wasn’t in it for any notoriety, though. He didn’t know a thing about pop culture and quite frankly didn’t care. “If it ain’t got that swing, it don’t mean a thing.”

There was an infamous moment in Pec history in 1992, when the uber famous U2 lead men came to the door. The girls they were with were very young looking and didn’t have IDs. The door man, pulled between being star struck and knowing Jerry’s strict expectations of checking everyone for IDs, nervously called him to the door. He told Jerry that it was U2, but they didn’t all have IDs. Before returning to work, Jerry matter-of-factly said, “well you two and the two bimbos can get the hell out then.” The entire bar had a great laugh about it and the jazz played on. The awkwardly hilarious situation made the paper the next day. Jerry never did find out what the big deal about U2 was.

In 1992, the City of Denver threw a literal curve ball at Jerry when they announced the construction of Coors Field, right at El Chapultepec’s front door. The construction would last two years and change a lot of the landscape surrounding The Pec. Buildings were demolished, viaducts were torn down, train tracks were removed, and some bars and restaurants started moving into the old warehouses. It was an exciting time, but nothing much changed inside the doors of The Pec. In April of 1995, Coors Field opened its doors. “LoDo” as it stands now, had not been developed yet and The Pec was still one of the only destinations for entertainment in the area. Jerry stayed the course with his vision. As time wore on, sports bars and restaurants filled every building and the changes started to be felt.

Kenny Borrego, Angela, Jennifer Levine, Tony Black, Dewey Adams, Chris Harris, and Jessica Jones.

Kenny Borrego, Angela, Jennifer Levine, Tony Black, Dewey Adams, Chris Harris, and Jessica Jones.

Chapter Three: Changing of the Guard

The Rockies crowds grew and the El Chapultepec patrons were being outnumbered by sports fans on game days. Parking was hard to come by and crowds were getting noisier. At some point in the early 2000s, Jerry came to realize that he had to adapt to the changes and he worked with drummer Tony Black to edge in some blues on the weekends. The younger, rowdier crowds related more to that, and while Jerry tolerated it, he still kept that straight-ahead jazz on no-game days and the off-season. As the years went on, Jerry aged as we all do. His daughter, Angela, was taking on more of the day-to-day operations. LoDo became fully developed as we know it now and jazz fans weren’t fighting the inconveniences to come visit. Angela started to add funk to the weekend line-up and the newer audiences loved it too. She never gave up on straight-ahead jazz either. At the very least, Freddy Rodriguez Sr kept one night a week for the standards. He would have to time breaks around the ball game release and mix in some cover tunes, but he made it work. Many musicians would still come sit in with Freddy and that night would renew Jerry’s soul. In 2012, Jerry passed away peacefully in his home, surrounded by his family. Even in our collective mourning, Angela kept The Pec afloat and gracefully took ownership of the operations. Jerry left behind big shoes to fill, but Angela did that and more. She took over booking the bands and all the invisible work that it takes to run a nightclub.

However, the changes in LoDo continued and it wasn’t easy to keep up. The city passed new ordinances that forced Angela to re-paint the iconic “Hot Burritos and Cool Jazz Nightly” mural because it exceeded the maximum number words allowed. The aging building required costly repairs regularly. Even though she didn’t own the building, Angela was responsible for the repairs. The crowds at closing time were large and unruly. Fights, shootings, and general chaos became common on that corner. Angela made more adjustments to protect the musicians and staff. Earlier closing times, providing a house drum kit so they wouldn’t have to attempt to load out, extra doormen at each entrance. El Chapultepec continued to be a great place despite all of these things, even winning Best Blues Club in Westword’s 2017 Best of Denver.

As we all know, in March of 2020 the world came to a stand-still due to COVID-19. Freddy Rodriguez Sr. played the last gig before the mandated shutdowns were announced. For the first time in four decades, El Chapultepec’s stage went dark. Freddy Rodriguez Sr. sadly passed away from complications related to COVID-19 and the entire Pec Family was heartbroken. Throughout the shutdown, Angela did everything she could to support her staff and musicians; including partnering with Dazzle to present live-streaming shows online, as well as opening for take-out meals. Financially, The Pec could weather the storm. It had survived the Great Depression, wars, financial recessions, and natural disasters. But the more development that surrounded El Chapultepec, the more it felt like a square peg in a round hole.

The COVID-19 shutdown gave Angela and the entire Krantz family time to reflect on how things were really going. If the patrons and musicians could not feel safe coming and going, if the music could not be heard over the cheers and jeers of sports fanatic crowds, if the building’s aging plumbing and electrical systems couldn’t stand another repair, was The Pec being true to Jerry’s vision? The question started to change from when to reopen to if it should reopen. Considering what El Chapultepec’s core values were and if they could continue to truly represent that, the painful ultimate decision was made. That landmark location could not continue to breed the excellence it was known for. Angela couldn’t swim upstream to preserve the memory of the ghosts that covered the walls. It was time to take a reprieve and decide how to honor and continue the legacy of El Chapultepec in New Denver. The city of Denver and the development of LoDo simply outgrew the jazz giant.

El Chapultepec Legacy Project logo

Chapter Four: Preserving The Legacy

The legacy of El Chapultepec has three cornerstone aspects. First, ensuring access to affordable-quality live music. Second, fostering a music environment that lends to improvisation organic interactions between different generations of musicians. Lastly, continuing to breed a community of musicians and music lovers from all races, genders, sexualities, and socioeconomic classes in a way that sheds pretense and embraces humanity.

Now the work of moving that legacy into the future starts. It is imperative to include as many patrons and musicians as possible. We hope to connect the community through this web site, El Chapultepec Piano Bar at Dazzle, and eventually a multi-media memory preservation project.

Thank you all for being a part of El Chapultepec’s Legacy, cheers to the next chapter.